|

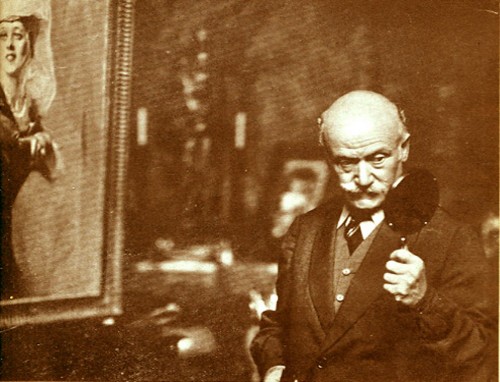

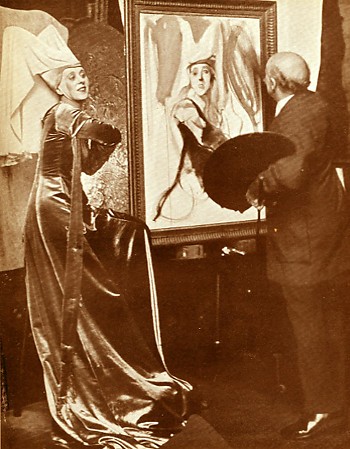

"Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies" by Philip de Laszlo

|

The

brilliant Hungarian artist, Philip Alexius de László,

1869-1937, was the successor (in 1907) to Sargent's portrait

practice in London. In 1933 de László demonstrated

his dashing technique in a series of photographs, while answering

questions posed by the writer A.L. Baldry. The photos and

text were published in 1934 by The Studio Publications of

London, in volume six of their "How to Do It" series.

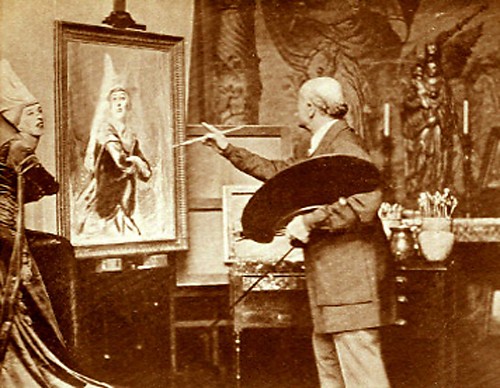

6. Accessories

Q: What about the rest of the portrait, the draperies

and accessories, how do they rank in relative

importance?

"Most of what I have just said about the

manner in which hands and feet reveal personality

applies to the movement of the sitter's body and,

I repeat, rightness in recording that movement

is necessary for the making of a successful portrait.

There is, in the pose he adopts an unconscious

assertion of himself, and the way he wears his

clothes emphasizes this assertion. A woman's dress,

a man's uniform, robes or everyday suit fall into

lines on the sitters themselves quite different

from those they would take on any model or lay

figure and so you may fairly say that the arrangement

of the draperies must be seriously studied because

in it is seen a further revelation of character."

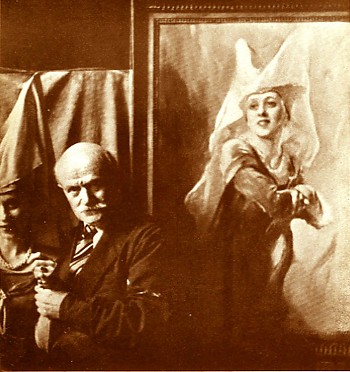

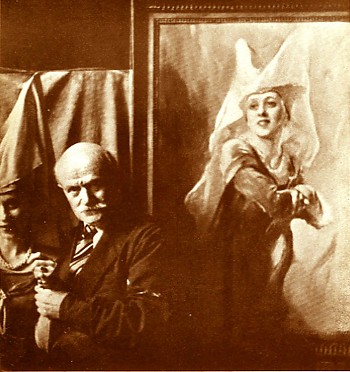

17. When to Stop

The

sitter, the

The

sitter, the

painter and the

completed por-

trait. In this

instance the

entire process

occupied only

eight and a half

hours.

Q: Is that why, as you put it, you develop

the general effect of your picture continuously?

"Yes; I say once more that by the time I

have finished the head I reckon to have brought

all the rest of the picture into harmony and right

relation with it without necessarily dwelling

upon the lesser details. That is the stage at

which this portrait of Miss Ffrangcon-Davies has

now arrived and there is, I think, no need to

carry it any further. It is an example of a type

of picture I often paint in which I concentrate

on the head and hands and leave the rest unelaborated

but, as nearly as possible, correct in forms and

values. Still, now that the head and hands are

finished, I could, if I wished, complete the draperies

and accessories with the help of a model or lay

figure, without losing the qualities of the picture,

because I have already painted all the main facts

of the draperies on the sitter. I might mention

that when I do paint a completely finished large

picture I endeavour to keep the draperies restrained

in tone so that, however rich the dress or uniform

and accessories may be, the attention of the spectator

is not diverted from the head and hands by any

over-insistence upon the incidentals."

Q: But surely your method is a little unusual.

Do many artists paint the draperies in their portraits

on the actual sitters?

"I really cannot tell you, but I am inclined

to think that a good many do not. You will often

see in a portrait that the head gives the impression

of not belonging to the body. This is generally

because the head has been painted throughout and

finished independently of the rest of the picture

and then the clothes on someone else's body have

been added to it. The result must almost inevitably

be a misfit, which is to be deplored. Of course,

the risk of over-tiring the sitter must be avoided

and for this reason I have always aimed at rapidity

and directness in my handling of the draperies

which the sitter wears. To paint a hand or foot

from a model and not from the sitter would be,

of course, unpardonable."

18. When a Fresh Start

is Necessary

Q: I can quite appreciate that rapidity and

directness are essential in all stages of work

like yours, but I can also imagine that if you

were not absolutely sure of yourself and knew

exactly what you meant to do they might easily

get out of control. What would happen if a picture

did not develop in the way that you intended?"

"Before I go into that I would like to point

out that no artist can ever be absolutely sure

of himself; even to pretend to think that he is

infallible would be a most dangerous form of conceit.

At no time can he afford to relax his effort to

acquire greater acuteness of vision and more complete

command over the technical processes of his craft.

Of course, because he is human, he will always

be liable to make mistakes, and he must constantly

be on his guard against them; and when they do

happen they must be frankly recognized and boldly

dealt with. I am convinced that when a piece of

work has gone wrong it is no good tinkering with

it and trying to pull it into shape. That only

makes things worse. For myself, if I am not content

with the way a portrait is developing, if from

the moment when I have made my first drawing I

cannot go straight ahead to a satisfactory finish,

I throw aside what I have done and begin again."

Q: What! Another picture on a fresh canvas?"

"What else? To find that I was not succeeding

in realizing my intention would mean that I could

no longer take pleasure in my work and decidedly

I should not feel inclined to waste my energies

on something that annoyed me. Besides, even if

I did fight my way out of the difficulty, all

the freshness and spontaneity of my picture would

be gone. With a fresh canvas I have a new problem

to solve and I can start with my way clear before

me. I have even, on occasions, discarded a half-finished

portrait and begun another because I chanced to

discover that my sitter had a more interesting

aspect that the one I had first chosen to paint.

It seems to me obvious that I should want his

portrait to show him at his best."

Q: Would it not be permissible sometimes to

improve on the original? For instance, when you

were painting a woman might you not idealize her

a little?

"Indeed, you surprise me! You are as bad

as a very mature lady who once asked me to paint

her, but insisted that I should make her look

like what she told me she had been when she was

twenty years younger."

Q: How amusing. Did you do it?

"Can you imagine my doing anything so ridiculous?

If I were so foolish as to start trying to improve

on nature what could I expect but an entirely

artificial and conventional result" In serious

portraiture there is no place either for what

you call idealizing or for that sort of caricature

which some people affect because they fancy that

a portrait gains in strength by over-accentuation

of the sitter's facial peculiarities. Very often

these peculiarities are wholly accidental and

have no significance whatever for the student

of the sitter's character, and by exaggerating

them a thoroughly false impression of his personality

might be given. The painter's mission is to find

and record intelligently the best and most characteristic

view of his sitter, not to make him look like

a freak."

Q: Do you think our modernist artists would

agree with you in that?

"To such a question I have nothing to reply.

I am not discussing the opinions of other people,

I am explaining to you what I believe. Whether

others do or do not agree with me has nothing

to do with the matter. I claim the right to think

for myself."

To be continued

The

sitter, the

The

sitter, the

Work

on

Work

on

Developing

Developing